The Way of Zen by Alan Watts is a book I had heard a lot about over the years but had never actually taken the time to read.

Similarly, the concept of “zen” is pervasive in popular culture yet I would argue that very few of us know what the word is referring to.

A quick disclaimer about everything in the key takeaways below: these notes are the parts of the book which spoke to me. I make no claims on it being a comprehensive overview of Zen Buddhism or of The Way of Zen. If the ideas below intrigue you, reading the book will give you a much better grasp of these (admittedly) difficult to verbalize ideas.

You can also listen to a deep dive discussion of this book from the Made You Think Podcast:

The Way of Zen Key Takeaways:

There Are Major Differences in the Basic Premises of Eastern vs Western Thought

Despite the fact that The Way of Zen is a book about “religion”, I found the first chapter of the book to be incredibly relevant to everyday life, and in my opinion, by far the best section of the entire book.

Conventional Knowledge

First and foremost, Watts wished to show that the “Eastern” way of thinking (whatever that means) is a far more fluid system than the Western thought system. Referring to the Western thought system, Watts said:

We do not feel that we really know anything unless we can represent it to ourselves in words, or in some other system of conventional signs such as the notations of mathematics or music.

At first, someone who grew up in a Western system may react against this and say something along the lines of, “Well duh. How do you know something if you can’t represent it?”. This will be addressed in more detail later but to the Eastern mind, things which can be represented are part of the “conventional knowledge” system, but are not the totality of overall knowledge. Conventional knowledge is applied in a wide-range of areas:

Roles

We have difficulty in communicating with each other unless we can identify ourselves in terms of roles – father, teacher, worker, artist, “regular guy”, gentleman, sportsman, and so forth. To the extent that we identify ourselves with these stereotypes and the rules of behavior associated with them, we ourselves feel that we are someone because our fellows have less difficulty in accepting us – that is, in identifying us and feeling that we are “under control”. A meeting of two strangers at a party is always somewhat embarrassing when the host has not identified their roles in introducing them, for neither knows what rules of conversation and action should be observed.

Anyone who has a slightly unconventional career knows exactly what Watts is referring to in the quote above. One of the most awkward questions to answer can be “what do you do?” if you don’t fit into any well-defined buckets.

Reality vs Narrative

I am also what I have done, and my conventionally edited version of my past is made to seem almost more the real “me” than what I am at this moment. For what I am seems so fleeting and intangible, but what I was is so final. It is the firm basis for predictions of what I will be in the future, and so it comes about that I am more closely identified with what no longer exists than what actually is.

From the actual infinitude of events and experiences some have been picked out – abstracted – as significant, and this significance has of course been determined by conventional standards. For the very nature of conventional knowledge is that it is a system of abstractions.

These quotes have a way of slapping you in the face with reality. When we are asked to describe ourselves, what do we do? We give a narrative of the things we’ve done in the past. And we don’t really have any option not to talk about things in the past tense – because the very act of describing requires us to name something concrete – which is really only possible for things that have already happened. And as the second quote says, we can’t share or value every moment equally so we tend to select certain moments that we view as “significant” to play a starring role in our narrative.

Complexity

These two concepts are presented in different sections of the book but are very much tied together. First, complexity:

We call our bodies complex as a result of trying to understand them in terms of linear thought, of words and concepts. But the complexity is not so much in our bodies as the in the task of trying to understand them by this means of thinking. It is like trying to make out the features of a large room with no other light than a single bright ray. It is as complicated as trying to drink water with a fork instead of a cup.

On one level, it’s not inaccurate to call something like the human body “complex”. There are so many moving pieces that even with millennia of study by some of the brightest minds in the world, we still don’t have a complete picture of how the human body works. But on another, more basic level, the human body isn’t complex at all. It simply is. The only reason we think it’s complex is because we are attempting to describe it using the abstraction of language.

Peripheral Vision

Watts uses a term to define how to understand “complex” things using intuition rather than linear, explicit thinking. He calls this the “peripheral vision” of our minds. These are the things we do without thinking about them. To be clear, there are many people who use this mode of “thinking” in Western society – for example athletes, artists. actors, even salespeople. But the point here is that peripheral vision is not an academically respected mode of thinking in the West. A doctor could never say “I’m recommending this procedure because I feel it is right” and a consultant could never make a client recommendation because she “feels it will work”.

As someone who grew up in the Western world and therefore, who has a Western mindset, my mind initially rebelled against this way of thinking. After all, it goes completely against our ideas of rational thought. But after further thought, I realized there are so many things we do every day that we couldn’t hope to put into words. For example, how do you move your arms? You just move them!

Overthinking

Something which comes up again and again in The Way of Zen is the negative effect of overthinking. The centipede parable from the book helped bring the point home for me:

The centipede was happy, quite,

Until a toad in fun

Said, “Pray, which leg goes after which?”

This worked his mind to such a pitch

He lay distracted in a ditch,

Considering how to run

This reminds of the weird phenomenon that happens when you stare at or repeat a word for too long and start thinking it’s spelled weird or sounds wrong.

Tao

The Tao which can be spoken is not eternal Tao

Someone could spend a lifetime thinking about the sentence above, and indeed some have. I’ve noticed an interesting theme come up several times with the books we’ve covered on the Made You Think podcast: there is this idea that as soon as you attempt to describe the nature of reality, it has shifted. The only question is: how much has it shifted? If it hasn’t shifted much, the difference (delta) between reality and your spoken reality may be so close that your spoken reality is essentially correct. But if it has shifted significantly, your spoken reality will be false. And I think that’s what this quote is trying to get at:

If you can speak of Tao, it isn’t Tao.

Wei vs Wu-Wei: Who Made The Universe?

Wei vs Wu-Wei is another concept from The Way of Zen that really caught my attention. Wei can be roughly translated to “making” and wu-wei to “not-making” or, more accurately “growing”. The best way to think about it is that things which are made are being put together by a maker but things which are grown divide themselves into parts from within. To put it bluntly: nobody “makes” a valley, forest, or mountain. These are produced by wu-wei. From the book:

Because the natural universe works mainly according to the principles of growth, it would seem quite odd to the Chinese mind to ask how it was made. If the universe were made, there would of course be someone who knows how.

But a universe which grows utterly excludes the possibility of knowing how it grows in the clumsy terms of thought and language, so that no Taoist would dream of asking whether the Tao knows how it produces the universe. For it operates according to spontaneity, not according to plan.

Zen Buddhism

It may seem odd that it took me 1,500 words to get to the Zen Buddhism part of a book called The Way of Zen. That’s how densely packed this book is though. Obviously there’s a lot I’m leaving out in this section but this is a high level overview. For a deeper discussion, go read the book!

The Basics

There are a few core Buddhist concepts that need to be outlined before diving into the Zen school of thought.

Duality

The dual nature of reality is a constant theme in Buddhism. The idea is that what makes up our world is actually pairs of opposites. For example:

- Light is inconceivable without darkness

- Order is meaningless without disorder

- Good is nothing without evil

- Up requires down

The state of nirvana or enlightenment in Buddhism is reaching a state beyond duality, which is an illusion (see below).

Maya

The idea of maya refers to the world of events and facts. Maya is referred to as an illusion and is very much tied to the idea of duality:

It will thus be easy to see that facts and events are as abstract as lines of latitude or as feet and inches. Consider for a moment that it is impossible to isolate a single fact, all by itself. Facts come in pairs at the very least, for a single body is inconceivable apart from a space in which it hangs. Definition, setting bounds, delineation– these are always acts of division and thus of duality, for as soon as a boundary is defined it has two sides.

An idea related to maya is the word rupa, which refers to form – physical or otherwise. This is considered an illusion because all form is impermanent.

Avidya

Avidya is the formal opposite of awakening. It is the state of the mind when hypnotized or spellbound by maya, so that it mistakes the abstract world of things and events for the concrete world of reality.

Avidya distinctly reminds me of the map vs terrain concept I’ve written about previously. This is a natural human tendency and one that must be actively fought.

Karma

Man is involved in karma when he interferes with the world in such a way that he is compelled to go on interfering, when the solution of a problem creates still more problems to be solved, when the control of one thing creates the need to control several others. Karma is thus the fate of everyone who “tries to be God.” He lays a trap for the world in which he himself gets caught.

The above quote from The Way of Zen might as well have been written by Nassim Taleb in his references to interventionistas.

The Limits of Thought

Can then thought review thought? No, thought cannot review thought. As the blade of a sword cannot cut itself, as a finger-tip cannot touch itself, so a thought cannot see itself.

This goes back to what was discussed earlier about the mind’s peripheral vision. Buddhism is very clear that the mind is not able to grasp itself.

Death

But the anxiety-laden problem of what will happen to me when I die is, after all, like asking what happens to my fist when I open my hand, or where my lap goes when I stand up.

The transient nature of the world is a theme which comes up again and again in Buddhism. Metaphors like the fist and the lap are used to help one realize the transient nature of their physical self and dissolve the ego.

Zen

The difference between Zen and other types of Buddhism is said best by Alan Watts:

Perhaps the special flavor of Zen is best described as a certain directness. In other schools of Buddhism, awakening or bodhi seems remote and almost superhuman, something to be reached only after many lives of patient effort. But in Zen there is always the feeling that awakening is something quite natural, something startlingly obvious, which may occur at any moment. If it involves a difficulty, it is just that it is much too simple. Zen is also direct in its way of teaching, for it points directly and openly to the truth, and does not trifle with symbolism.

If the goal of Buddhism is to move beyond maya or desire, then it doesn’t make sense to “strive” for enlightenment. Striving would just be another form of desire. As Watts says:

The attempt to work on one’s own mind is a vicious circle. To try to purify it is to be contaminated with purity. Obviously this is the Taoist philosophy of naturalness, according to which a person is not genuinely free, detached, or pure when his state is the result of an artificial discipline. He is just imitating purity, just “faking” clear awareness.

In this way, Zen is logically consistent in a deeply satisfying way.

Other Eclectic Tidbits

There were a few other concepts in The Way of Zen which really caught my attention but don’t fit neatly into other buckets.

Who Decides?

We feel that our actions are voluntary when they follow a decision, and involuntary when they happen without decision. But if decision itself were voluntary, every decision would have to be preceded by a decision to decide-an infinite regression which fortunately does not occur. Oddly enough, if we had to decide to decide, we would not be free to decide. We are free to decide because decision “happens.” We just decide without having the faintest understanding of how we do it. In fact, it is neither voluntary nor involuntary.

This section is both spooky and super fun to think about. It’s also very much tied to the concepts of strange loops in Godel, Escher, Bach. I especially find it fascinating that this ancient Buddhist concept of transcending duality (voluntary vs involuntary) can be found in something as practical and “of this world” as the decision-making process. This topic has become even more relevant in recent years as humans attempt to design machines and artificial intelligence.

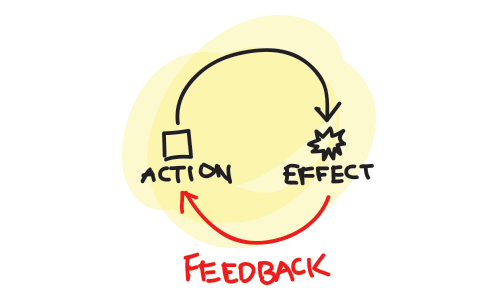

Feedback Loops

Feedback controls are found in the engineering of systems, particularly in systems with automatic controls. The basic idea is for a machine to be informed of the effects of its own actions in such a way as to be able to correct its action.

From the book:

The proper adjustment of a feed-back system is always a complex mechanical problem. For the original machine, say, the furnace, is adjusted by the feed-back system, but this system in turn needs adjustment. Therefore to make a mechanical system more and more automatic will require the use of a series of feed-back systems– a second to correct the first, a third to correct the second, and so on.

But there are obvious limits to such a series, for beyond a certain point the mechanism will be “frustrated” by its own complexity.

Similarly, when human beings think too carefully and minutely about an action to be taken, they cannot make up their minds in time to act.

This is very much related to the Optionality Trap concept I’ve written about extensively. Overthinking leads to an inability to act.

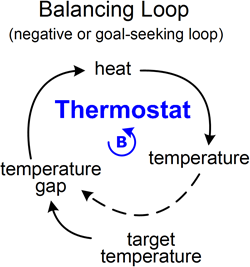

The Thermostat Analogy

The thermostat analogy is a related one. Thermostats operate within a temperature range – not at a precise temperature. For example, if you set your thermostat to 70 degrees, it will operate the furnace within a range of perhaps 68 and 72 degrees. When the temperature cools off to 68, the furnace will receive a signal to “turn on” and raise the temperature to 72, at which point it will receive a signal to “turn off”. At first glance, this temperature range seems silly. Why not just keep the temperature at 70 degrees?

The answer goes back to feedback loops. If you tried to keep the temperature at 70 degrees, the thermostat signals for the furnace to “turn on” and “turn off” would be exactly the same and the machine would be ineffective. The system needs a certain amount of “slack” between the input and output in order to be function.

Once again, this analogy is spot on as it relates to the human mind. From the book:

We saw that when the furnace responds too closely to the thermostat, it cannot go ahead without also trying to stop, or stop without also trying to go ahead. This is just what happens to the human being, to the mind, when the desire for certainty and security prompts identification between the mind and its own image of itself. It cannot let go of itself. It feels that it should not do what it is doing, and that it should do what it is not doing. It feels that it should not be what it is, and be what it isn’t. Furthermore, the effort to remain always “good” or “happy” is like trying to hold the thermostat to a constant 70 degrees by making the lower limit the same as the upper.

The desire for certainty and control is the equivalent of setting the thermostat at 70 and not allowing any “give”. The machine (in this case, the mind) shuts down.

Final Thoughts

Considering the difficulty of the topic, The Way of Zen is a surprisingly easy and pleasant read. What isn’t easy, however, is understanding the subject.

As you can probably tell, a lot of the concepts in this book are difficult to put into words. This makes Alan Watts’ accessible work all the more remarkable. The notes above are my best interpretation of the topics presented. It was, of course, impossible to cover everything or go into as much detail as the book. I’m sure Alan Watts would have a similar lament – there is an infinity to these subjects that cannot be fully grasped by the human mind.

And that’s where the fun is.

****

Pick up your copy of The Way of Zen on Amazon or wherever you buy books and let me know what you think in the comments or on Twitter.

You can listen to Nat Eliason and I discuss the concepts from The Way of Zen on an episode of the Made You Think Podcast.

For more book recommendations, sign up for my monthly reading recommendation newsletter.

9 thoughts on “The Way of Zen Key Takeaways”

Comments are closed.